Aftershock of the New: Woodblock Prints of Post-Disaster Tokyo (1928–32)

The shockwave struck at lunchtime. Witnesses would later state that tremors rocked Tokyo for ten full minutes, igniting fires across the city as lit stoves and cooking oil were thrown together in the chaos of the magnitude-7.9 earthquake. With water mains severed, the resultant blazes spread unchecked across the largely timber cityscape, consuming everything in their wake as the winds whipped them onwards. By the time the aftershocks petered out and the last flames were extinguished, the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, as it would come to be known, had claimed over 100,000 lives — including thousands of ethnic Koreans and others murdered amidst xenophobic rumors of sabotage — and the face of Japan’s capital had been altered forever.

Yet in the aftermath of this tragedy, the tone of many bureaucrats and public planners in Tokyo was one of optimism, almost cheer, at the vast expanses of burnt-over nothingness that now provided them with space in which to lay out broad new roads and grand civic buildings in imported styles. This is the vision put forward in One Hundred Views of New Tokyo (Shin Tokyo Hyakkei), a collection of prints by eight artists published between 1928 and 1932. The artists who contributed to the series were part of the sōsaku hanga (creative print) movement, which brought new techniques and aesthetic vocabularies to the Japanese woodblock. “Sofar as the classical ukiyo-e artists are concerned, I feel positively no relation to them and no debt to them whatever”, said Onchi Kōshirō, one of the movement’s most famous exponents and a leading contributor to the New Tokyo series. “Today our attitudes toward art are completely different.”

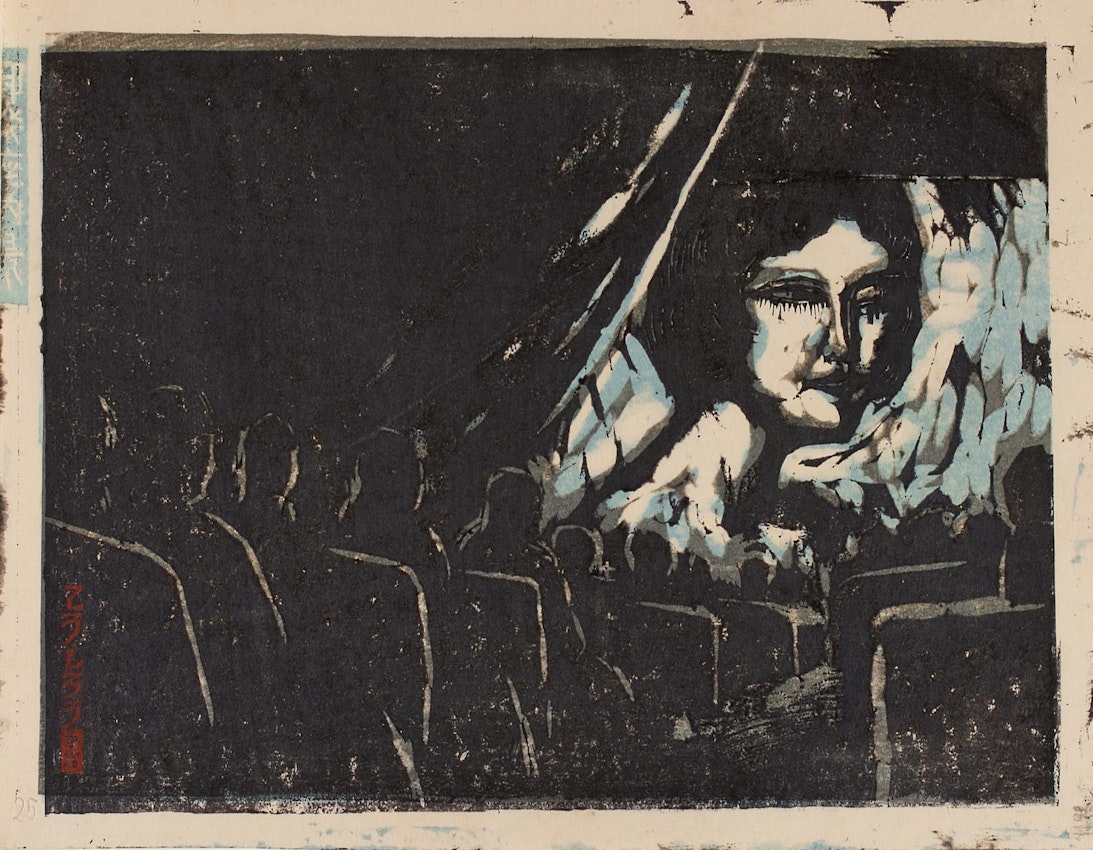

One can detect in Onchi’s declaration something of the functionary’s heady glee at the leveled quakescape’s infinite potential — that “forceful reiteration of modernity’s logic of creative destruction,” in Gennifer Weisenfeld’s words, “aimed at legitimating urban development and renewal.” Yet despite the artist’s strenuous disavowals, parallels to prints of centuries past are not hard to spot. The series participates in a long lineage of ukiyo-e celebrating (and skewering) vistas of the so-called Eastern Capital — taking as its most direct point of reference Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo Hyakkei, 1856-9). Pagodas are traded for church domes, the pine-needle fires of tile kilns for a smokestack’s laminar effluent, and a fisherman’s net is replaced by the protective mesh screening fans at a baseball field. Like Hiroshige, who set many of his series’ prints during ombré hours, the artists of Shin Tokyo were also interested in exploring the play of light, though in their case it is not the firelit congress of foxes that interests them but the splayed image of a film projector in a darkened theater.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Onchi Kōshirō, Inside of a Cinema, 1929

One of the cardinal visual effects of Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo is its recurring, often winking inclusion of foreground elements that loom over and even eclipse whatever well-known site the print in question is supposed to be elegizing: a suspended turtle, a boatman's hairy arm, the groin of a straw-shod horse. Against the calligraphic swish-swish of a black koi banner, does anyone even notice the diminutive arc of Suidō Bridge, whose celebration is the image’s pretext for existing in the first place? This is the crux of Hiroshige’s message: an Audenesque affirmation that these great and exalted places exist amidst — and indeed owe the great force of their vitality to — the quotidian moments that they stage and that here upstage them. But the views of New Tokyo exhibit neither Hiroshige’s stylistic preference nor the sentiment that undergirded it. No person, no animal, and not a single thing can rival the city itself, which is the protagonist above all else. It’s notable how many of the series’ people look away from the viewer, into the distance or out at the great capital that has already opened its mouth to consume them. It’s noteworthy, too, that the later series drops Hiroshige’s word meisho (famous places) from the title. Many of its views — the Shell station, the thronged dance hall — could be from nearly anywhere at all, speaking little to Tokyo but a great deal to the shin, the new, the now.

If the earthquake shook the city loose from the particularities of space, it also disjointed it from time: Shin Tokyo’s artists did not, as Hiroshige did, divide their series according to the march of the seasons, and in the enclosed worlds of the subway station and the gleaming department store, who can tell if it is day or night? Time is no longer cyclical, per Hiroshige’s vision — instead we have only the great forward tilt toward modernity, which like sugar on the tongue entices only to dissolve once you have finally gotten a taste. Indeed, less than two decades later, when a number of the prints were reissued in the wake of Japan’s surrender to the United States, it was under the self-consciously wistful title Tokyo Kaiko Zue, often translated as Scenes of Lost Tokyo. Yet in another sense the prints had lost their shin even before they were first published. “Yesterday’s Tokyo has already changed, and there are many prints in the early part of the series showing places that have changed. So they are really ‘Old’ Tokyo and not ‘New’ Tokyo”, wrote the artist Maekawa Senpan, who contributed twelve prints, in an article on the occasion of the series’ completion. “Indeed, we could [already] start on another series of Shin Tokyo Hyakkei!” This is Audenesque too, in a sense, though perhaps transposed into a different key: how everything turns away quite leisurely from the disaster.

Maekawa Senpan, Suijo Park in Daiba, 1930

Henmi Takashi, Hijiri Bridge, 1930

Maekawa Senpan, Night Scene at Shinjuku, 1931

Fukazawa Sakuichi, Meiji Baseball Stadium, 1931

Maekawa Senpan, Miniature Golf, 1931

Fukazawa Sakuichi, Rising Sun Shell, Showa Street, 1931

Kawakami Sumio, Aoyama Cemetery, 1929

Henmi Takashi, Road Leading to the Meiji Shrine, 1931

Henmi Takashi, Botanical Gardens, 1929

Maekawa Senpan, Department Store, Shibuya, 1929

Henmi Takashi, Kagurazaka, 1929

Suwa Kanenori, Asakusa, 1930

Kawakami Sumio, Inside the Department Store, 1930

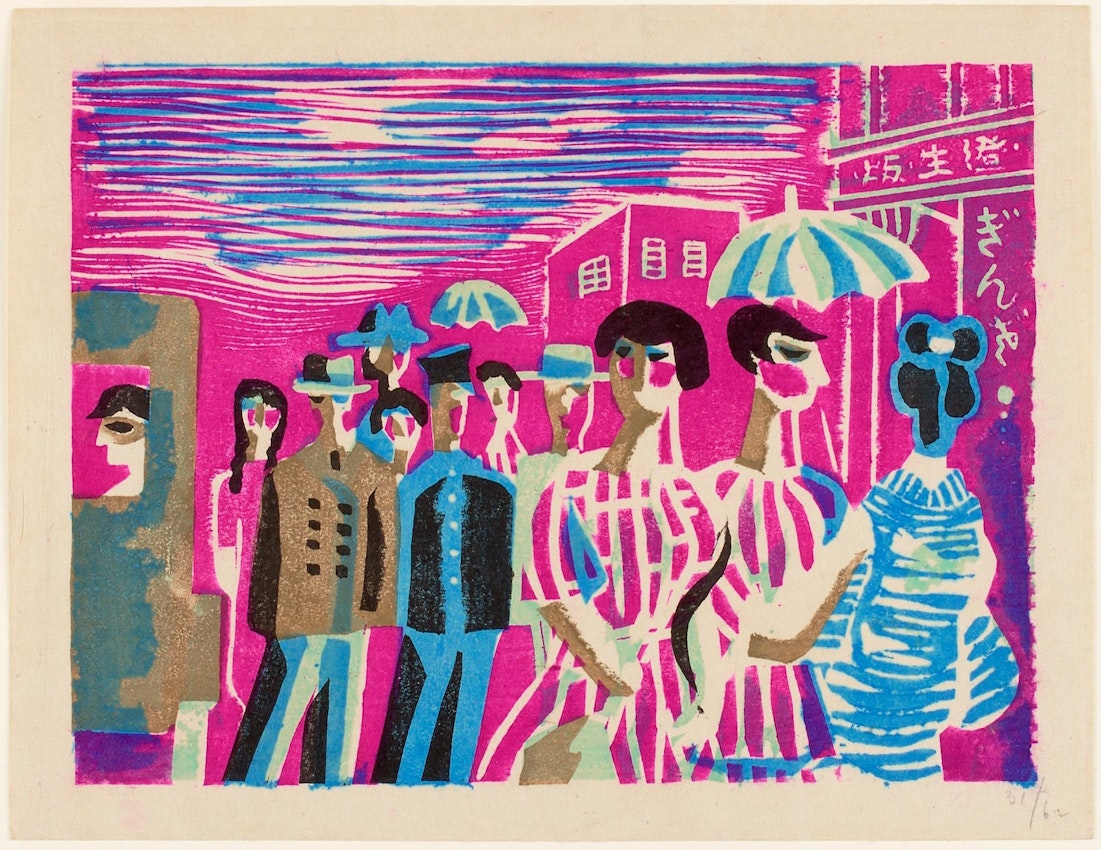

Kawakami Sumio, Ginza, 1929

Kawakami Sumio, Asakusa Park, Casino Follies, 1930

Onchi Kōshirō, Inside of a Cinema, 1929

Kawakami Sumio, Chrysanthemum Show, Hibiya Park, 1930

Onchi Kōshirō, Hibiya Open Air Music Hall, 1930

Fujimori Shizuo, Atagoyama Radio Station, 1929

Fukazawa Sakuichi, Cafe District in Shinjuku, 1930

Fujimori Shizuo, Central Meteorological Observatory, 1929

Kawakami Sumio, Hamarikyu Park, 1931

Fukazawa Sakuichi, Yanagi Bridge, 1929

Fujimori Shizuo, The Kabuki Theatre at Night, 1930

Kawakami Sumio, Military Grand Parade, 1929

Kawakami Sumio, Okuma Memorial Hall, Waseda University, 1930

Kawakami Sumio, Fish Market, 1931

Suwa Kanenori, Mitsubishi in Marunouchi, 1929

Henmi Takashi, Imperial Hotel, 1930

Henmi Takashi, Park at Hongo Motomachi, 1931

Henmi Takashi, Rain in Yotsuya-Mistuke, 1930

Onchi Kōshirō, Dance Hall Scene, 1930

Maekawa Senpan, Subway, 1931

Onchi Kōshirō, Twilight Scene at the Flood Bank of the Inogashira Pond, 1930

Suwa Kanenori, Imperial Diet Building, 1932

Suwa Kanenori, Fukagawa Garbage Incinerator, 1930