In the Mind of Marie: A Haunting Encounter in the Gardens of Versailles (1913)

In 1901, two British women just getting to know each other took a trip to Paris. The day they visited Versailles, things turned strange. They were wandering in the gardens, hoping to find Petit Trianon, a smaller palace that had been the home of Marie Antoinette, when they began to see unusual things: people in antiquated clothing, a man with dark, pitted skin, a breathless servant delivering an urgent message to a woman sketching on the ground. The atmosphere was strange too, heavy and unsettling. Things seemed flat and otherworldly; Moberly wrote later of feeling “an extraordinary depression” and a “dreamy, unnatural oppression”. In time, the women joined a tour group, and the feeling went away. Everything felt normal again. The whole incident couldn’t have lasted more than thirty minutes.

A week later, the women agreed that the Petit Trianon was probably haunted, and decided to separately write down what they remembered of their walk. When comparing notes, they found some conspicuous differences. Charlotte Moberly had seen a woman in plain sight right near the path, for instance, whereas her companion, Eleanor Jourdain, had no recollection of this person. Both found these discrepancies intriguing, and decided they were part of the queer uncanniness of the whole incident.

Jourdain and Moberly worked at the Oxford women’s college St. Hugh’s. At the time of the Paris visit, Moberly was fifty-five and headmistress; Jourdain, eighteen years younger, was her incoming assistant. It was a few months later, when Jourdain was researching her lesson on the French Revolution, that she discovered their visit to the gardens happened on the 109th anniversary of the Storming of the Tuileries Palace — the day that Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI had watched the slaughtering of their guards, and were imprisoned. Some Parisians, Jourdain learned, believed Versailles was haunted on this particular day.

This set their wheels turning, but it didn’t quite make sense. Jourdain and Moberly had not witnessed a violent takeover, but a prosaic afternoon. Then the two women, who had by now become quite close, had a creative epiphany: perhaps they hadn’t visited the actual events of August 10th, 1792, but the mindscape of Marie Antoinette on that day.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Stereograph by Florent Grau titled Petit Trianon in the Gardens of Versailles, 1858 — Source.

According to Jourdain and Moberly’s theory, as the Queen was on tenterhooks, awaiting execution, she naturally reflected back — as anyone in her position might do — to the first time she’d been told of a threat to the crown. That had happened three years previously, in 1789. Jourdain and Moberly found a description of this scene in a book written by a gardener’s wife, who was present. Antoinette had been sitting in her favorite grotto when a servant ran up to tell her there was a mob approaching the castle. This was precisely what Moberly and Jourdain had witnessed! “We had inadvertently entered within an act of the Queen’s memory”, the two concluded. No wonder they’d felt entrapped — they had been trapped: in the despondent mind of Marie Antoinette. It was time travel with a hairpin twist; they’d landed in the psyche of a woman in 1792 who was thinking about 1789.

Jourdain and Moberly were astonished when the Society for Psychical Research dismissed their story as lacking credibility. They resolved to marshal evidence, and spent the next nine years on elaborate, painstaking research. Through interviews, archival sleuthing, and repeated visits to France, they coaxed facts from the woodwork. The women “proved”, for instance, that the plow they’d noticed was from an earlier era; that a door they’d heard slam hadn’t been unlocked for at least a century; that Marie Antoinette’s personal bodyguards wore coats of the grayish green color they remembered; that her seamstress had made her a green silk bodice and semi-transparent white fichu exactly like they’d seen. Some far-off violin music was decisively identified as eighteenth-century light opera, and the incidental children were matched to the age and gender of the gardeners’ children. The women’s archival zeal brokered no limits. They tracked down records of payment for the clearing of dead leaves, the material composition of 1780s shoe buckles, and the gardeners’ method of eradicating invasive caterpillars.

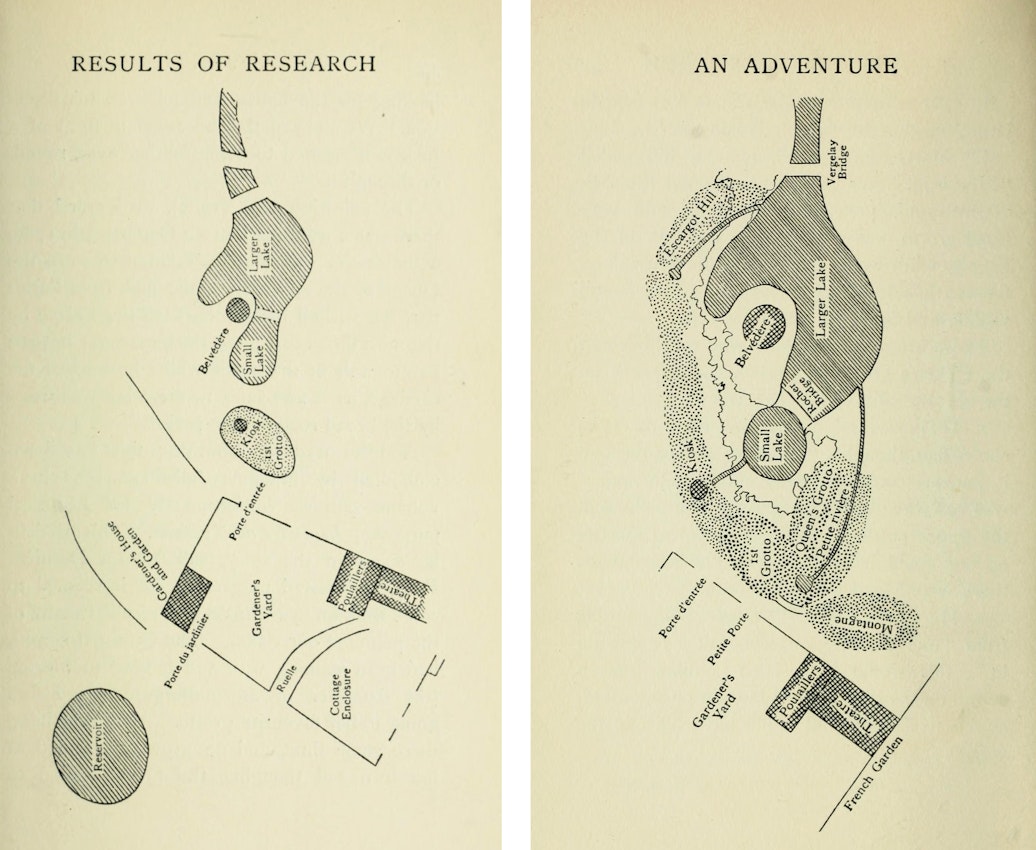

In Moberly and Jourdain’s eyes, this crazy-quilt accretion of labyrinthian detail cemented their case. Thus armored, they decided to publish An Adventure (1911), an account of their experiences. The book was furnished with a timeline, appendices, copious footnotes, and even several archival maps, intended to prove that Moberly and Jourdain’s walking path was solely consistent with Versailles’ 1789 landscaping. An Adventure was very popular; 11,000 copies sold in the first two years, and it went through at least six subsequent editions.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Two of several maps reproduced by Charlotte Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain in An Adventure.

The story doesn’t end there, however, because Jourdain and Moberly’ obsessive fixation had the curious effect of soliciting their readers’ own obsessive fixation. Terry Castle’s essay about the affair describes An Adventure as transmitting an “infection” — an infection that caused normal people to pore over minutiae for years on end, so as to take impassioned sides in what would seem to be a very low-stakes argument. Article after article, and even, unbelievably, book after book, debated whether Moberly and Jourdain were telling the truth. To subsequent editions of An Adventure the co-authors added yet more “proof”, which fanned the controversy instead of settling it.

The most salacious of the takedowns, according to Castle, was published by a former student of the pair: Lucille Iremonger’s 1957 The Ghosts of Versailles. (By this point, Moberly and Jourdain had been dead for two decades, but the debate raged on; the saga was the occasion of a London symposium a year later.) Iremonger dropped two bombshells. First, that the two women, contrary to what they publicly claimed, had had various other paranormal experiences. Iremonger alleged that Moberly had privately described many apparitions, including visions of medieval monks, the Roman Emperor Constantine wandering the Louvre, the spirit of her dead father as a dazzling white bird. Jourdain also had visions, though they were more paranoiac; in fact, she died of a heart attack after she convinced herself that her staff was plotting mutiny.

The other revelation was that the two women were lesbians. Iremonger alleged that their relationship was exactly like that of “husband and wife”, and detailed who was dominant in what respect, going so far as to speculate the dynamics of their affinity. Naturally, Iremonger brought up homosexuality to impugn the women’s credibility, but nowadays, the allegation reads differently. In a saga awash in detail, this detail bobs above the others.

What really happened? Here’s one version: two women of uncommon intelligence spent decades asserting the validity of their particular shared experience. They fought tooth and nail to prove that they saw what they saw, that it mattered, that it was real, and that they were credible. It was an argument about ghosts, but it might not have been about ghosts at all.