C. P. Cranch’s Very Literal Illustrations of Emerson’s Nature (ca. 1837–39)

Christopher Pearse Cranch (1813–1892) is remembered for bringing levity to Transcendentalism. At the various gatherings that soldered the movement, the good-looking Cranch played the flute and guitar, loved to sing loudly, and pretended to talk to animals. “We have transcendental and aesthetic gatherings at a great rate”, he reported to his sister, “and they make me sing at them all. I have worn my Tyrolese yodlers almost to the bones . . . I am quite a singing lion.” Cranch was also quick with the pen, making witty sketches on the spot. His best party trick was to sketch satirical illustrations of sentences plucked from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature (1836) — a book that Cranch and his friends admiringly devoured. Emerson’s earthy, concrete analogies invited image-making.

It started one evening, when Cranch and a friend, the minister and publisher James Freeman Clarke, began illustrating various Emerson quotes by literalizing the author’s figurative language. The two men doodled and giggled, so much so that when the visit ended, they continued to exchange drawings in the mail. Cranch was the more skilled artist, and Clarke egged him on. Clarke collected some of the drawings into a scrapbook, titled Illustrations of the New Philosophy, and sent others round to friends — all people who revered Emerson and received the satire with its intended geniality. The sketches were passed among Transcendentalist-leaning social circles in New York and Boston to the point that Cranch bragged, “My drawings . . . permeate all houses, as water doth a sponge. Wherever I go I hear of them.” Clarke also sent a selection directly to Emerson, who received the caricatures not as an insult, but an overture of friendship. Emerson and Cranch soon became lifelong friends.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

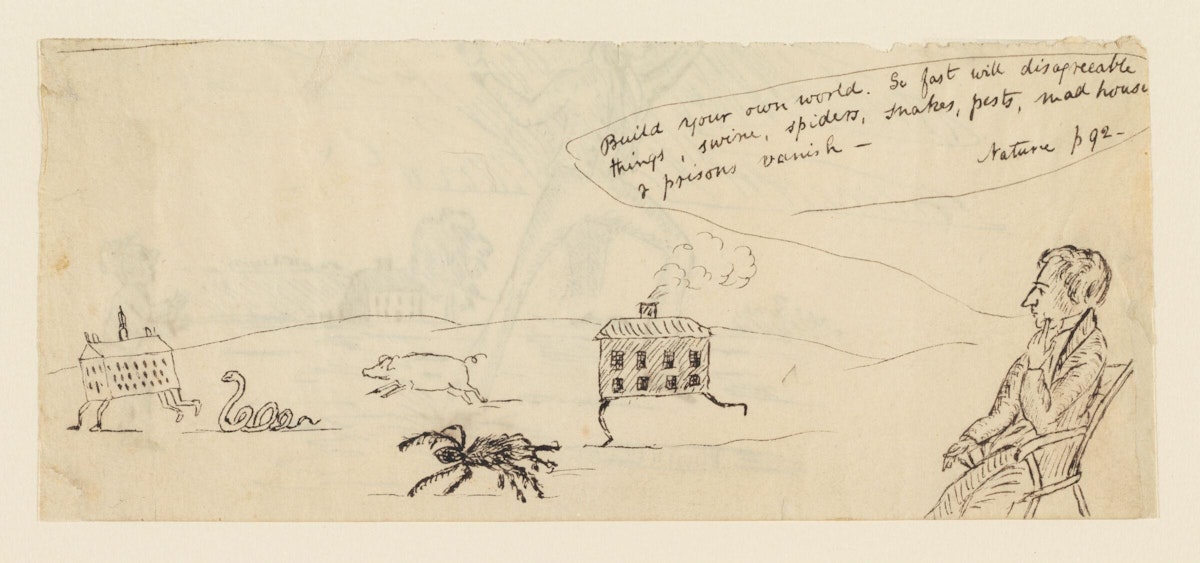

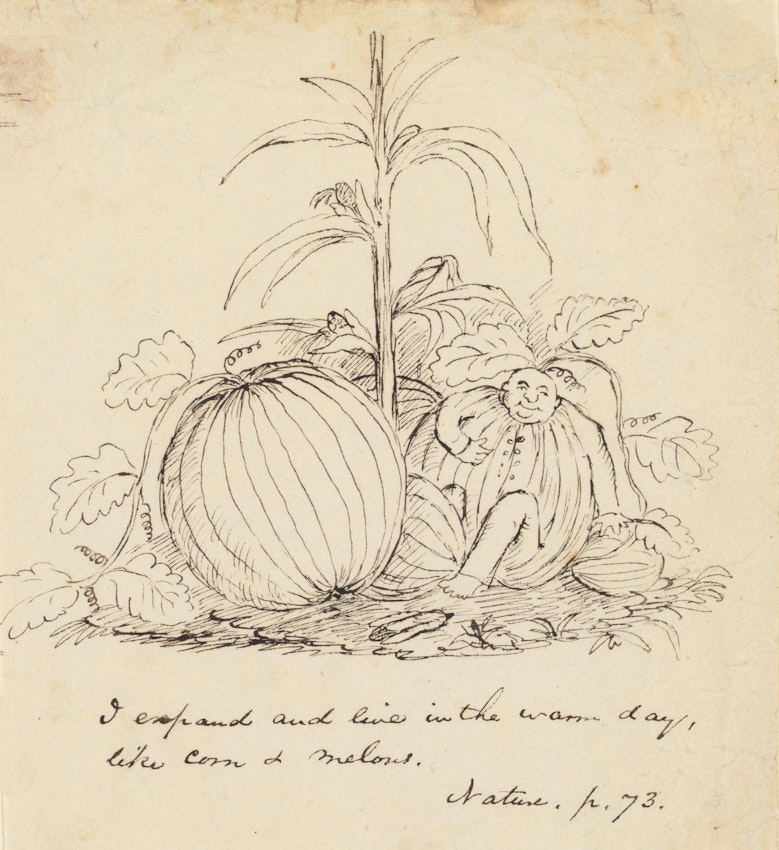

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Christopher Pearse Cranch, illustration to Emerson's Nature captioned “I expand and live in the warm day, like corn & melons”, ca. 1837–39

The sketches were cheeky, teasing, and toothless. They deflated Emersonian pretention, but were clearly the product of genuine delight — Cranch found Emerson’s language lively and fresh, and the drawings were his simpatico reply. One of the most popular depicted Emerson’s head perched atop a giant ridged melon, captioned with the Nature quotation, “I expand and live in the warm day, like corn and melons.” Others were similarly straightforward. When Emerson said in an address at Harvard, “Men in the world today are bugs”, Cranch drew a horde of upright insects, and when Emerson exclaimed “How they lash us with those tongues of theirs!” Cranch drew eight rope-like tongues and a cowering victim. Cranch’s illustration of “Few grown-up persons see the sun” is precisely what it says: a cluster of learned adults clueless to the radiance above. Even when the satire was more acerbic, it was a joke among friends. One such doodle, now lost, depicted Margaret Fuller driving the Transcendentalist carriage, reins in hand, with Emerson lounging in the back seat.

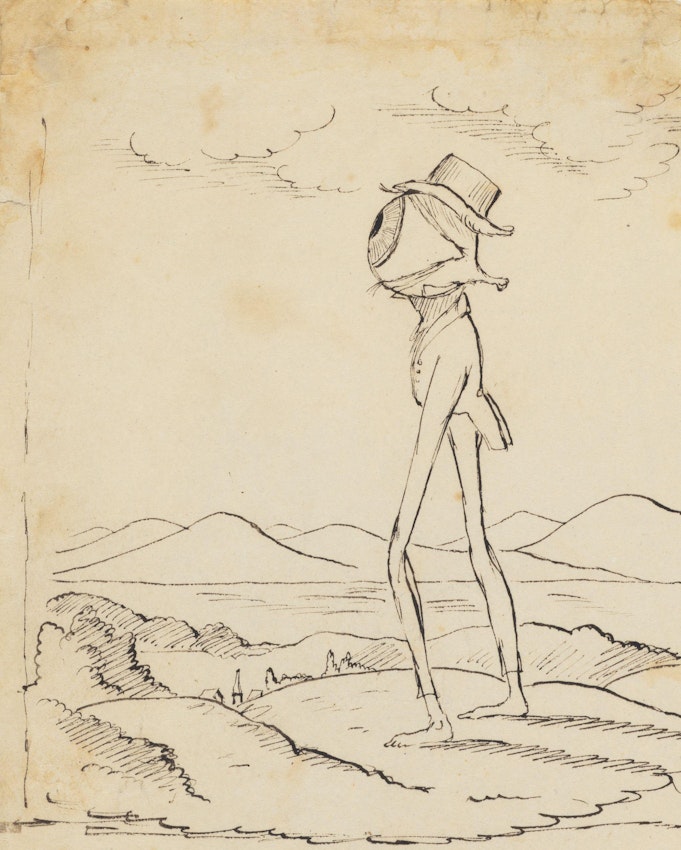

The best known of Cranch’s sketches is the “transparent eyeball” drawing. The version featured below shows an eyeball in a dinner jacket and top hat, his optic nerves forming a low ponytail. It was shrewd of Cranch to home in on this baffling phrase. Eyeballs perceive transparency, but aren’t themselves transparent, so what did Emerson mean? Context helps, a bit. “Transparent eyeball” appears near the end of Nature’s first chapter, when Emerson is trying to describe precisely why walking in the woods has a curative effect.

Standing on the bare ground,— my head bathed by the blithe air,— and uplifted into infinite space — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

Bodily dissolution is key to these enchanted moments, except the body can’t entirely dissolve, because one part of the body — the eyes — induces the dissolution. “I am nothing; I see all” is the operational tangle that leads Emerson to the paradoxical “transparent eyeball”. Cranch’s illustrative figure is appropriately at odds with itself. Its posture is debonair, and its hands seem to have melted away, but its large eyeball-head, with barely the suggestion of a lid, stares upward, rapt and transfixed, as if communing directly with the sun.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Christopher Pearse Cranch, illustration to Emerson's Nature captioned “Standing on the bare ground, - my head bathed by the blithe air, & uplifted into infinite space, - all mean egotism vanished. I become a Transparent Eyeball”, ca. 1837–39

Some scholars have described these jottings as the pinnacle of Cranch’s life achievement. That’s a little harsh, but it’s true that Cranch’s cleverness never begat an illustrious career. He came from a prestigious, accomplished family that was deeply intertwined over three generations with that of President John Adams and his son, President John Quincy Adams. (John Adams and Cranch’s grandfather married two remarkable sisters, Mary and Abigail Adams; Christopher Pearse Cranch married John Quincy Adam’s sister.)

Cranch was less conventional than his father, grandfather, and brother, and less impelled to do things he didn’t like doing. The poet and abolitionist James Russell Lowell described his friend thus: blessed with “gifts enough for three—only his foolish fairy left the brass out when she brought her gifts to his cradle.” As a young man, Cranch entered the ministry, but spoke with too much diffidence to be a charismatic preacher. He was never ordained, and instead traveled, taking the pulpit for short stints in different cities. His burgeoning interest in Transcendentalism threatened what thin career prospects he had, and after his dear friend and fellow Transcendentalist John Sullivan Dwight was forced to resign the ministry, Cranch quit in solidarity, and burned his sermons.

With no training of any sort, he announced at age thirty that he would become a landscape painter. Unfortunately, his talent was middling. A “major mediocrity” is how he’s described by his biographer. Cranch’s unorthodox career left his wife and family of three children perpetually short on funds. They couldn’t afford to live in New York — where “greenbacks melt like snowflakes on hot griddles”, Cranch complained in 1863 — and so they settled for a decade in Paris. Cranch painted a great deal, but he also translated Virgil, published poems and reviews in The Dial and other magazines, and wrote two novels for children. He corresponded with many distinguished friends, and penned opera star Jenny Lind’s adieu to her American audiences. But nothing stuck. Few of his paintings sold, and his four books of poetry landed too quietly. One of them, ill-advisedly titled Satan, reportedly sold not a single copy.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

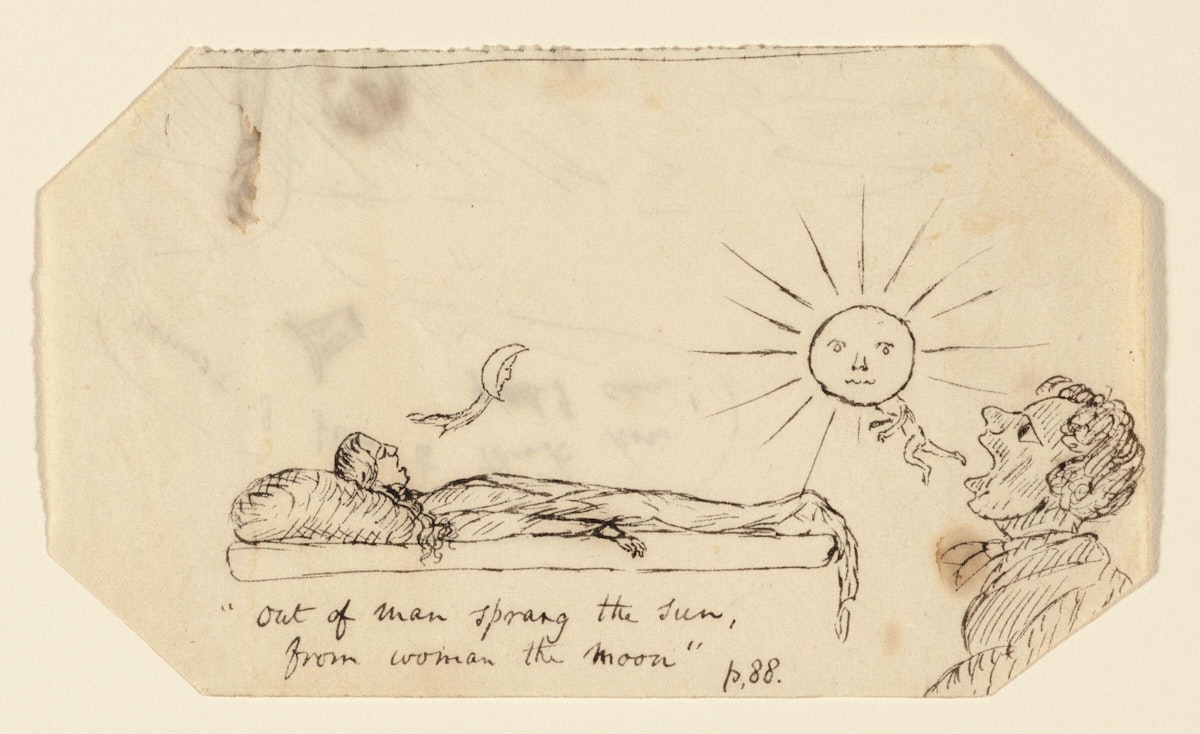

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Christopher Pearse Cranch, illustration to Emerson's Nature captioned “Out of man sprang the sun, from woman the moon”, ca. 1837–39

Like many humorists, Cranch was privately melancholic, and his depressive stints deepened as he aged. A posthumous tribute in Harper’s Magazine bluntly noted that Cranch was often silent and withdrawn. Certainly he had cause: the strain of his financial struggles, his artistic mediocrity, the fact that his father was mortified by his association with the Transcendentalists; the premature death of two sons.

Cranch himself, however, said the “blues” were simply part of his character, and always had been. For relief, he looked to music, and also to Emerson. Cranch could recite pages of Nature aloud; the book reliably lifted his spirits for four decades. Thirty-five years after the satirist and his subject went huckleberry picking together on Walden Pond, Cranch sent Emerson a new landscape painting to thank him for a lifetime of solace. “I owe you for all that your works have been to me.”

Below you can browse a selection of Emersonian sketches from Illustrations of the New Philosophy (ca. 1837–39), the scrapbook assembled by James Freeman Clarke in Cranch’s name.

Two Figures

Cover of Illustrations of the New Philosophy

“I expand and live in the warm day, like corn & melons”

“Standing on the bare ground, - my head bathed by the blithe air, & uplifted into infinite space, - all mean egotism vanished. I become a Transparent Eyeball.”

“The great man angles with himself. He needs no other bait.”

“Men in the world of today are bugs.”

“They are content to be brushed like flies from the path of a great man”

“The man has never lived that can feed us ever”

“We are lined with eyes. We see with our feet.”

“This is my music - this is myself.”

“Build your own world. So fast will disappearable things, swine, spiders, snakes, pests, mad house & prisons vanish”

“How they lash us with those tongues of theirs!”

“Let him not quit his belief that a popgun is a popgun, though the ancient & honorable of the earth affirm it to be the crack of doom.”

“Few grown-up persons see the sun.”

“Cradle & infancy, school a playground, the fear of boys, & dogs, & females, the love of little maids & berries...”

“The ambitious soul sits down before each refractory fact.”

“Out of man sprang the sun, from woman the moon”

“The Priest becomes a form; the attorney a Statute Book; the mechanic a machine; the sailor a rope of a ship”