Indian Sign Talk (1893)

Upon reading Lieutenant Colonel Garrick Mallery’s 1880 appeal for descriptions of “Indian Sign Talk”, Lewis Francis Hadley abandoned his philological research on Quapaw and Ponca languages (he was reputed to know twenty Native tongues) and applied himself to the mastery of the single silent language that he estimated was known by over 100,000 Native people. By 1890, he had moved to a cave near Anadarko, Oklahoma. His tent was crowded with a printing press and stacks of woodblocks, which he carved with a kitchen knife to illustrate the hand language of Plains Indians. From woodblocks, he moved on to electrotype prints of his gestural sketches, which he made into flash cards that could be used to teach the signs. By the time he published Indian Sign Talk (1893), Hadley had printed more than 100,000 cards, and missionary friends had produced another 27,000 cards expressly for teaching Christian scripture.

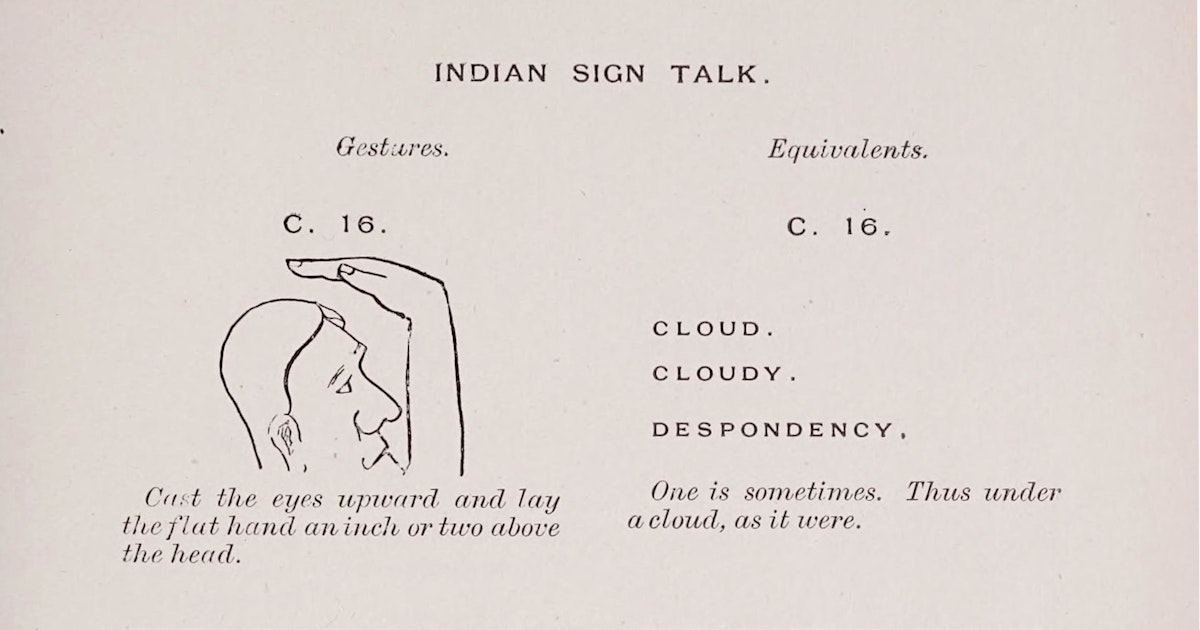

Indian Sign Talk begins with a vocabulary of over five hundred words which pair Hadley’s sketches of signs with telegraphic “equivalents” that spell out the thoughts behind the gestures. Noting that “the real genius of gesture language is grace, and ease”, Hadley shows how the language's syntax follows an economical set of grammatical rules: articles, conjunctions, and prepositions are omitted; adjectives follow nouns; verbs are always present tense. By surveying or practicing these sketches of things, events, and qualities, one feels an intuitive pantomimic impulse lying behind nearly every sign. For “bread”, pat imaginary dough between the hands; for “cat”, push the end of the nose upward with the ball of the right hand; for “cloud”, cast the eyes toward the sky, laying a flat hand above the head. Hadley occasionally gives lovely metaphorical extensions of these signs. The “cloud” gesture is used also for despondency: “One is sometimes . . . under a cloud, as it were.”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The multivocality of hand gestures emerges in Hadley’s brief commentaries: to sign “accost”, one holds the right hand aloft and rocks the wrist:

This may mean: Who are you?

What tribe do you belong to?

What are you doing?

Where are you going?

Or other inquiries, depending much upon circumstances at the time. One is often obliged to think well before answering this sign.

Crooking both index fingers and resting them on the sides of the head above the ears gives “cattle” and “horns”; turning the fingers outward means “buffalo”, by which he means bison — the sacred beast whose centrality to Plains culture actually birthed the gestural language. Hadley was among the first to recognize that the geographic extent of sign language coincided with the range of the American bison, whose nomadic habit brought hunters from all the Native nations of the Great Plains into perennial contact with each other. At its peak, Plains Sign Language stretched from what is now central Canada across the United States to northern Mexico, moving across hands between the Fraser River and the Rio Grande.

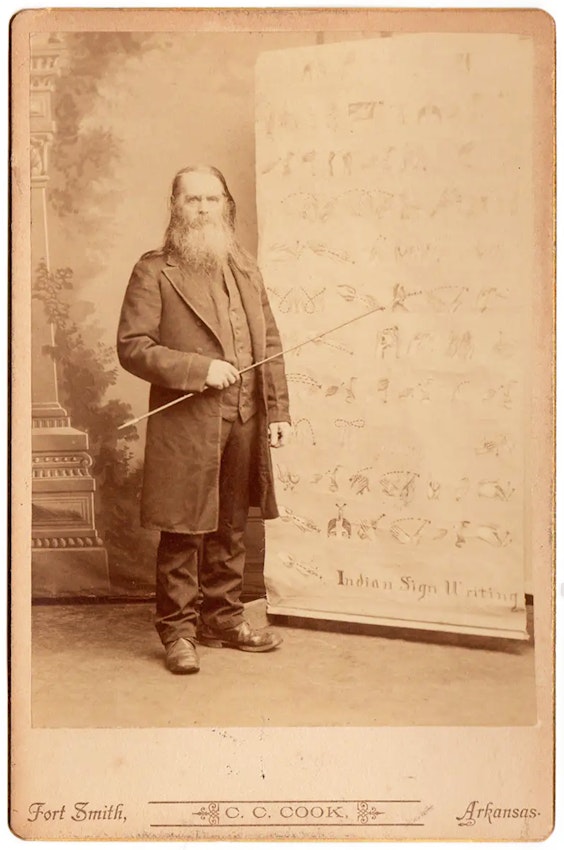

Born in 1829 into a Quaker family in Salem, Massachusetts, Hadley’s western travels initially brought him to live on boats – including one of his own design and construction – up and down the Arkansas River, whose course he spent two years charting. An early stenographer, his aptitude for rapid communication and mapping seemed to feed his passion for signs. Initially finding Indigenous customs “repugnant”, reported an Arkansas resident, Hadley later preferred to be called by his adopted name Ingonompashi (Long-Haired Sign Talker), and advocated practically “going native”, albeit for missionary ends: “If we try to reach the Indians’ tepee, and never go out of the white man’s road, we will never get there.” In an account of meeting Hadley during this period, a writer remembered him accidentally stirring cheese into a cup of tea, mistaking it for a sweetener he had not encountered in some time. “You see on the reservations we have only brown sugar”, he explained.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Photograph of Lewis Francis Hadley teaching “Indian Sign Writing”, ca. 1885 — Source.

The second section of Indian Sign Talk gets to the heart of Hadley’s mission to teach the Christian gospel. Beginning first with a gestural rendering of “The Indians’ Little Star” (“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”) and “Wolf and White Man” — a satirical story he witnessed being signed in plain sight of those mocked — Hadley moves on to a suite of Biblical texts including the Beatitudes, the Lord’s Prayer, and Psalm 19. Some sense of how keenly Hadley desired that his book be put to use as a tool to convert Native Americans to Christianity comes from a section entitled “Receive Jesus Now”. Hadley’s subtitle claimed Indian signs to be an “Almost Universal Gesture Language”, which was exactly why it held so much appeal for him as a communicative bridge to his own deeply held universal language of Christian scripture. Hadley's later biography is unknown. A 1949 article in Chronicles of Oklahoma records that, after publishing Indian Sign Talk, the rest of his life and death “remains a mystery”.

Below you can browse a selection of the 268 octavo plates from Hadley’s Indian Sign Talk. And you can watch a 1930 documentary clip of the language being used on Wikipedia.