Karl Blossfeldt’s Urformen der Kunst (1928)

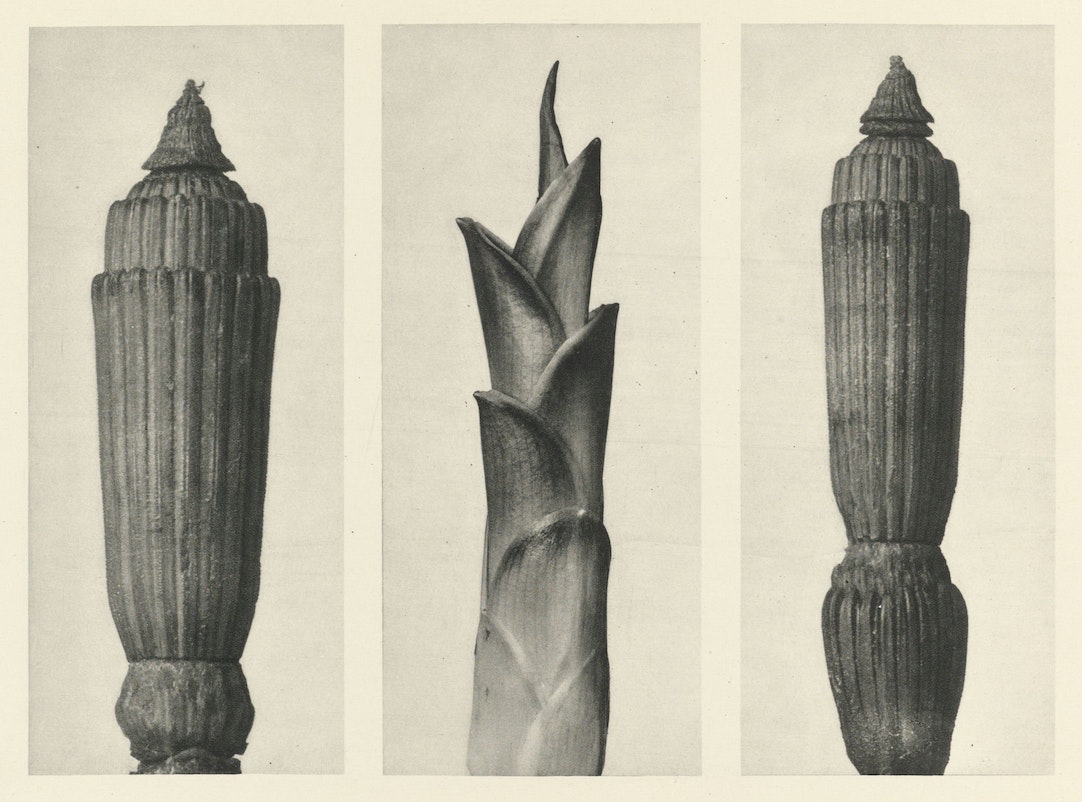

At the grand old age of 63, just four years before his death, Karl Blossfeldt produced his first photography book, the internationally best-selling Urformen der Kunst (later translated into English as Art Forms in Plants). The book's 120 plates display Blossfeldt's remarkable photographs of plants – varieties from Equisetum hyemale (Winter Horsetail) to Tellima grandiflora (Fringe cups) — all captured in extraordinary detail, as if under the microscope, frozen into new forms almost beyond recognition.

Born in 1865 in Germany’s Harz Mountains, Karl Blossfeldt lived a childhood in the open air. As a teenager he became an apprentice in a foundry making wrought iron grilles and gates, objects decorated with plant-motifs, before then moving to Berlin to study at the School of the Museum of Decorative Arts. In 1890, he moved to Rome to study under the decorative artist Moritz Meurer, where he created and photographed casts of botanical subjects, travelling as far as North Africa to collect specimens. From 1898, and for the next three decades, Blossfeldt taught design at Berlin's School of the Museum of Decorative Arts. It was here, using a homemade camera with custom magnifying lenses, that he first began to take his remarkable photographs, for the purpose of teaching his students about the patterns and designs found in natural forms. Through the technology of photography Blossfeldt was able to reveal to his students details difficult to see by the naked eye. As he wrote in a 1906 letter to the school's director:

Plants are a treasure trove of forms — one which is carelessly overlooked only because the scale of shapes fails to catch the eye and sometimes this makes the forms hard to identify. But that is precisely what these photographs are intended to do — to portray diminutive forms on a convenient scale and encourage students to pay them more attention.

In light of this mission to reveal overlooked beauty, it is perhaps fitting that Blossfeldt chose not to obtain his specimens from florists or botanical gardens, but rather from track sides and railway embankments, what he called “proletarian areas”. In this sense, the photographs also stand as strange memorials to long-forgotten patches of land. These plants, many weeds, originally "out of place", now find refuge within the corpus of photographic history, immortalised upon the page.

When the gallerist and collector Karl Nierendorf came across Blossfeldt’s vast collection of photographs, he sought to publish them — Urformen der Kunst is the result. Though we know only a few hundred images today, largely selected by Nierendorf, it was thought that Blossfeldt had taken as many as 6000, many hung from the walls of his Berlin studio. In his introduction to the first edition, Nierendorf writes that Blossfeldt finds a “happy permeation” of three elements: nature, art, and technology. It is a common trope, oft-repeated in relation to Blossfeldt’s work. According to Hans Christian Adam, Blossfeldt strips nature down.

Blossfeldt might have used a fairly basic camera, but the results are startling. The plants become graphic, geometric. One cannot help but draw parallels between Blossfeldt’s Urformen der Kunst and Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur, published a couple of decades prior. In both works, the distinction between nature and art blur. Both depict nature in such detail, with such magnitude, that it appears as almost artificial, as an artwork. Indeed, upon closer inspection it is revealed that Blossfeldt did in fact sometimes retouch his photographs to emphasise and enhance the beauty of the forms he sought to celebrate.

Blossfeldt’s work was quiet and unassuming, but it quickly aligned with the avant-gardes of Weimar Germany: from "New Vision" to "New Objectivity". It provided a counterpart in the natural world to what others had attempted to achieve in the excess of the modern city: from the work of August Sander to László Moholy-Nagy. The critic Walter Benjamin was one of the first to review Blossfeldt’s book, claiming his fellow German had discovered the "optical unconscious": that which was invisible to the naked eye, revealed retrospectively or technically through the apparatus of the camera. In this sense, Blossfeldt completes Goethe’s idea of the Urpflanze — a primordial plant that contains within itself an infinity of potential forms: when dogwood becomes a bishop’s staff, when horse-chestnut shoots become totem poles, and the curly stems of the fern become iron railings. It is an art of revelation — "new objectivities" of nature revealed through the camera.

Urformen der Kunst was the first of three photo books by Blossfeldt: four years later there came Wundergarten der Natur (1932), and posthumously Wunder in der Natur (1942). All of Blossfeldt's published photographs have been collected in the highly recommended 2014 book from Taschen, Karl Blossfeldt: The Complete Published Work.