Maps Showing California as an Island

If California were a country its economy would be the fifth largest in the world (just ahead of the UK). Yet the tech boom is not the starkest way California has ever stood apart from its neighbours. That would surely be the maps depicting it as an island, entire of itself. Below we have featured our pick of these glorious seventeenth- and eighteenth-century aberrations, from a collection of hundreds held at Stanford.

The intriguing story of how the maps came to be deserves a little mapping itself. In the 1530s Spanish explorers led by Hernán Cortés encountered the strip of land we now know as the Baja Peninsula. They mistook it for an island and called it California. Both the name and the notion of it being an island came straight from the pages of a novel — a very popular Spanish romance, Las Sergas de Esplandián [The Adventures of Esplandián] (1510), which described an imaginary realm ruled by Queen Califia:

Know, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons. They had beautiful and robust bodies, and were brave and very strong. Their island was the strongest of the World, with its steep cliffs and rocky shores. Their weapons were golden and so were the harnesses of the wild beasts that they were accustomed to taming so that they could be ridden, because there was no other metal in the island than gold.

In 1539, a Spanish expedition led by Francisco de Ulloa discovered that the Baja Peninsula was just that, a peninsula, firmly attached to the mainland. And for the next eighty years published maps reflected this correct view. Then, in 1622, European maps suddenly started showing California adrift, effectively extending the Gulf of California in its northwesterly direction until it meets the Pacific. This island view of California, resembling a floating carrot, was replicated again and again over the next century and a quarter. By 1747, Ferdinand VI of Spain had had enough. He issued a reasonably clear decree, “California is not an Island”. But the royal newsflash travelled slowly. California would appear as an island as late as 1865 on a map made in Japan (see very final image below).

What on earth had happened? How had such a large piece of America been wrenched free? The Spanish clergyman Antonio de la Acensión played a crucial role. Two decades after sailing along the West Coast in 1602–3, Acensión began arguing in letters and books that California was an (enormous) island. It seems he wanted to extend the Gulf of California a great deal further north and so invalidate Sir Francis Drake’s claim of "Nova Albion" for England (as Acensión's version would have had Drake landing on the island of California, rather than the mainland). Acensión's island view was believed by many in Europe. And in the early 1620s maps showing California as an island started appearing in Spain and Holland. The first English one appeared in 1625, next to an influential article about the search for the Northwest Passage. From there the error took flight, deceiving map makers and readers throughout the world for decades.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

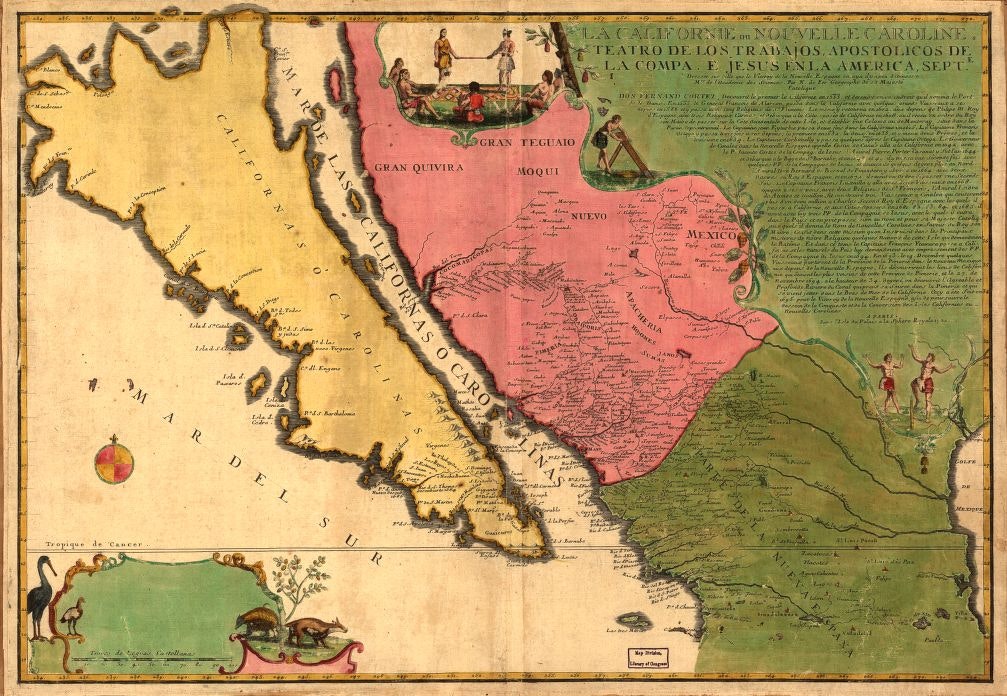

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.La Californie ou Nouvelle Caroline : teatro de los trabajos, Apostolicos de la Compa. e Jesus en la America Septe, by Nicolas de Fer, 1720 — Source.

The fact that a number of explorers knew that California was not an island was not enough to nip the idea in the bud. Yet it would be a shame to think of the idea as simply an error, a cartographical crease which needed ironing out. Even though maps may be presented as accurate, they cannot escape their metaphorical nature. They reflect much more than physical geography. That California was mapped as an island for so long speaks to its separateness. The writer Rebecca Solnit, a student of the Stanford maps, has argued that, “An island is anything surrounded by difference.” The state contains around 2,000 plant species found nowhere else. Its borders comprise dizzying mountains, harsh deserts and immense ocean. It has been home to the Gold Rush, the psychedelic era, the silicon boom. In several ways then, California is an island.

In 2018, nearly 400 years after the Island of California first appeared on a map, tens of thousands of Californians are supporting “Calexit” – the secession of the Golden State from the United States. As far as we know, none has advocated digging a mighty trench along the state borders and flooding it with Pacific moat water. For the foreseeable future at least, California is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

If you want to delve deeper into the story, there is an enjoyable chapter on it in Simon Garfield’s On the Map: Why the World Looks the Way it Does (2012). If you’d prefer to dive deeper still, we suggest The Island of California: A History of the Myth (1995) by Dora Beale Polk. Finally, if you’re just really into islands that are not actually islands, take a look at the improbable story of Sandy Island, which was only “undiscovered” in 2012.

Below you'll find featured our highlights from the wonderful Glen McLaughlin Collection of California as an Island, a collection of nearly 750 maps obtained by Mr. McLaughlin over nearly 40 years, which have all been digitised and made available under a public domain mark through Stanford University Libraries. The two maps shown above are both from the Library of Congress.

AMERICA with those known parts in that unknowne worlde both people and manner of buildings Discribed and inlarged, by John Speed, 1626 — Source.

La Californie Ou Nouvelle Caroline, Teatro De Los Trabajos, Apostolicos De La Compa, E Jesus En La America, Septe, by Nicolas de Fer, 1720 — Source.

Magnum MARE del ZUR cum Insula CALIFORNIA. De Groote ZUYD-ZEE en't Eylandt CALIFORNIA, by Reiner and Josua Ottens, 1745 — Source.

AMERICA cum supplementis poly-glottis, by Johann Baptistca Homann, 1741 — Source.

A Map of all the EARTH and how after the Flood it Was Divided among the Sons of Noah, by Joseph Moxon, 1711 — Source.

Audienca De Guadalajara, Nova Mexico California, &C, Nicolas Sanson, ca. 1657 — Source.

America, by Pieter van den Keere, ca. 1646 — Source.

'The Entire Planet Devoid of Water, Seen on Two Sides', by Thomas Burnet, ca. 1700 — Source.

Facies Terræ Americana in Luna Conspecta, John Seller, ca. 1700 — Source.

KAART der REYZE van drie Schepen naar het ZUYDLAND in de Jaaren 1721 en 1722, ca. 1720-1729 — Source.

World Map, by Heinrich Scherer, ca. 1700 — Source.

Novveav Mexiqve Et Californie, by Allain Manesson-Mallet, 1684 — Source.

Americas, by Johann Baptist Homann, 1719 — Source.

North America, by George Pratt, 1690 — Source.

Map of America, supposedly from Japan (though possibly from China), 1865 — Source.