Mazes and Labyrinths (1922)

If we wish to outline an architecture which conforms to the structure of our soul […], it would have to be conceived in the image of the Labyrinth. – Friedrich Nietzsche, Dawn (1881)

William H. Matthews’ Mazes and Labyrinths, published in London in 1922, is itself labyrinthine: a vast and richly illustrated encyclopaedic portrait of these mysterious phenomena across time and space; from the Minotaur of Crete to the great cathedrals of Medieval France to the stately homes and spiritual nuclei of England.

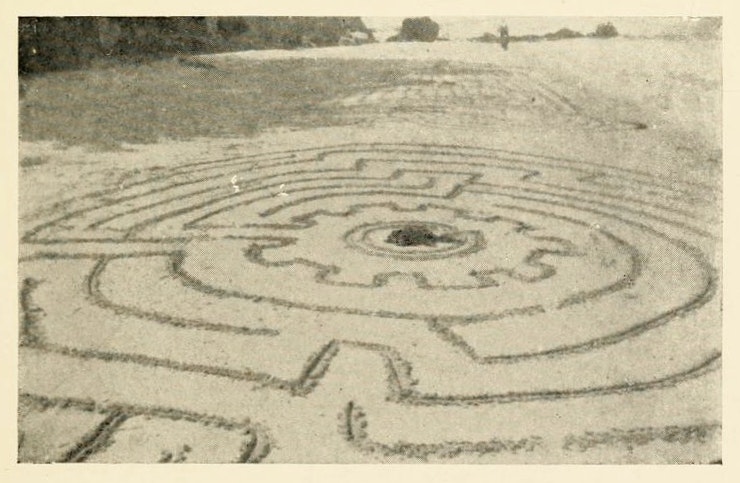

Opening the book, one of the first things the reader finds is the dedication: to the author’s daughter Zeta whose “innocent prattlings on the summer sands of Sussex inspired its conception”. The preface reveals the nature of her prattle, a question as to “who made mazes first of all” . Towards the end of the book we are shown photographs of the beach mazes made for Zeta to explore, photographed before she'd discover them and make them "invisible".

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.So much is revealed in the book’s dedication: the allure of the maze, how it occupies a curious space between rationalism and mysticism that attracts the child and the adult alike. From the childhood of civilisation to the childhood of us all, the maze proves a mysterious presence, a thing to explore but also avoid. It's an ambivalence reflected in the varying roles they've played over the millennia: from the twists and turns of the medieval church maze meant to echo the spiritual journey, at its centre “heaven”, to the maze experienced as hell, an imprisonment and torture.

While flattered by her father’s dedication, in her later years Zeta herself attributes her father’s interest in mazes to his time in the First World War, the battlefields of which he left for in the year she was born. Although she surmises the seed to be his learning of a destroyed church maze on the Arras Front, one can’t help wondering if his experience of the labyrinth-like trenches may have played a role too. Whatever the seed, he was clearly hooked and, according to Zeta, "within two and a half years of returning from France he had researched, written, printed and published this book". A remarkable feat considering its breadth of scope and depth of exploration — and that he was on somewhat unchartered territory, it being the first book dedicated to the subject.

As for Zeta’s question on the origins of these structures, her father is unable to offer a definitive answer. "The boundaries of knowledge are still misty and ill-defined", he writes in the conclusion, but for him this is a quality which only makes mazes all the more attractive, "a circumstance that only gives zest to the subject".

Imagery from this post is featured in

Affinities

our special book of images created to celebrate 10 years of The Public Domain Review.

500+ images – 368 pages

Large format – Hardcover with inset image