Photographs of a Falling Cat (1894)

Certain scientific circles of the nineteenth century were home to a rather unexpected preoccupation: the dropping of cats. While at university in Trinity College, Cambridge, James Clerk Maxwell, who would go onto become arguably the greatest theoretical physicist of the nineteenth century, was reportedly well known for the activity. In a letter to his wife reflecting on this reputation he'd earned, Maxwell wrote, "There is a tradition in Trinity that when I was here I discovered a method of throwing a cat so as not to light on its feet, and that I used to throw cats out of windows. I had to explain that the proper object of research was to find how quick the cat would turn round, and that the proper method was to let the cat drop on a table or bed from about two inches, and that even then the cat lights on her feet." He was not the only prominent scientist to be intrigued by the question of how cats, when falling from a height, seemingly were able to defy the laws of Newtonian physics and change motion in mid air to land on their feet. At around the same time, the eminent mathematician George Stokes was also prone to a spot of "cat-turning". As his daughter relates in a 1907 memoir: "He was much interested, as also was Prof. Clerk Maxwell about the same time, in cat-turning, a word invented to describe the way in which a cat manages to fall upon her feet if you hold her by the four feet and drop her, back downwards, close to the floor."

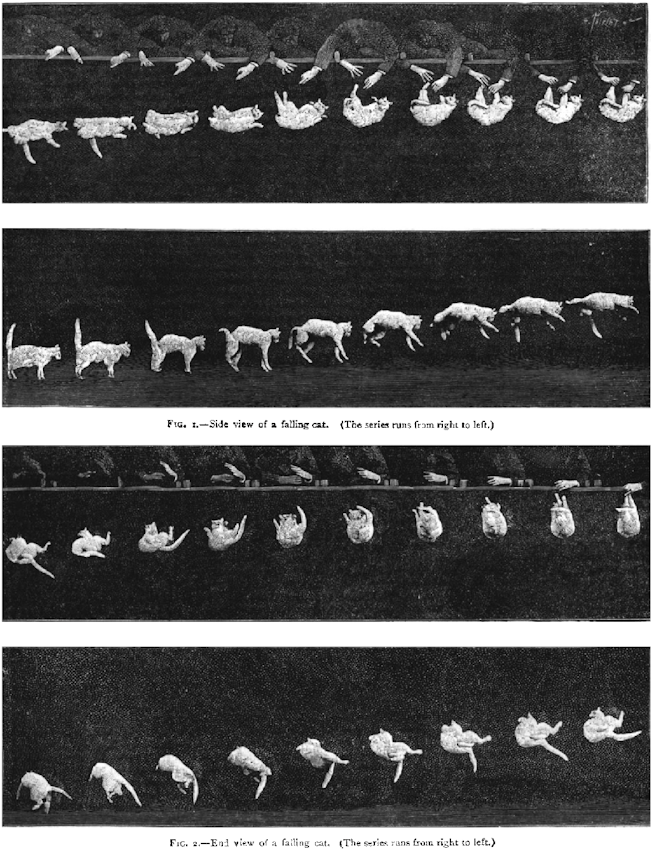

Despite the many falling cats, neither Maxwell nor Stokes made much headway in their investigations. It wasn't until some decades later, with the invention of chronophotography (which allowed many photographs to be taken in quick succession), that a more rigorous study could be applied beyond the limitations of the human eye. The man to do it was the French scientist and photographer Étienne-Jules Marey who in 1894 created a series of images from which he was able to make some important deductions. The images pictured below, captured at 12 frames per second, debunked the idea that the cat was using the dropper's hand as a fulcrum in order to begin the motion of turning at the beginning of the fall. Rather, the pictures showed that the cat had no rotational motion at the start of its descent and so was somehow acquiring angular momentum while in free-fall. Marey published these pictures, and his investigations, in an 1894 issue of Comptes Rendus, with a summary of his findings published in the journal Nature in the same year. The latter summarises Marey's thoughts as follows:

M. Marey thinks that it is the inertia of its own mass that the cat uses to right itself. The torsion couple which produces the action of the muscles of the vertebra acts at first on the forelegs, which have a very small motion of inertia on account of the front feet being foreshortened and pressed against the neck. The hind legs, however, being stretched out and almost perpendicular to the axis of the body, possesses a moment of inertia which opposes motion in the opposite direction to that which the torsion couple tends to produce. In the second phase of the action, the attitude of the feet is reversed, and it is the inertia of the forepart that furnishes a fulcrum for the rotation of the rear.

In a rather humorous turn the author of the article also states that "The expression of offended dignity shown by the cat at the end of the first series indicates a want of interest in scientific investigation."

Despite Marey's seemingly clear photographic evidence, many physicists continued to believe that the cat was using the dropper's hand as a fulcrum. It would be more than 70 years later until the riddle was finally solved, in Kane and Scher's 1969 paper "A dynamical explanation of the falling cat phenomenon". For more info on how the cat manages it see the great Wikipedia entries under "Falling Cat Problem" and "Cat Righting Reflex" (both of which include a handy diagram) and also this video from Smarter Everyday.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.