Shores of the Polar Sea (1878)

When the British Arctic Expedition set sail from Portsmouth on May 29, 1875, the explorers hoped to reach the highest latitude, and perhaps even approach the ever-elusive North Pole. It was believed that, should they successfully pass through Smith Sound, between Greenland and Canada’s Ellesmere Island, they would encounter an Open Polar Sea free from troublesome ice. With this primary goal, three steamships set out across the stormy Atlantic only to immediately become separated by a violent cyclone, reconvening at Disko Bay on the western coast of Greenland some weeks later. Perhaps they could have interpreted this early inconvenience as a sign of the winter to come, or a warning that the Arctic waters are rarely kind. Regardless, the captains pressed on.

In Shores of the Polar Sea, Edward L. Moss, an artist and esteemed Royal Navy Surgeon, records this journey from his first-hand seat in the belly of HMS Alert. A mixture of intimate journal entries, miscellaneous engravings, and sixteen chromolithographs, the book provides a unique, often surreal, retelling of life on the ice. Moss prefaces his work with a modest appeal: “Whatever may be the artistic value of the Sketches — and they lay claim to none — they are at least perfectly faithful efforts to represent the face of Nature in a part of the world that very few can ever see for themselves.”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

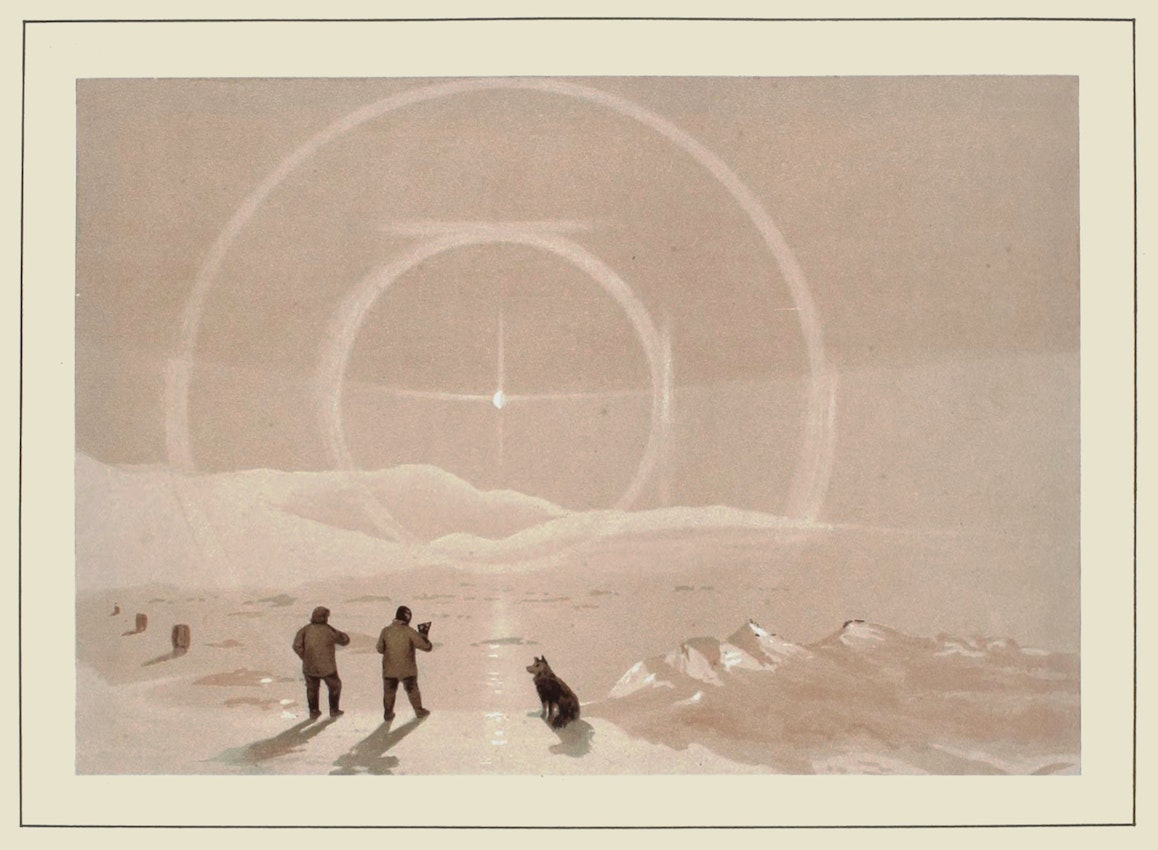

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“This is a sketch, from the floes alongside the ship, of an unusually distinct Paraselena that appeared on 11th December, 1875. The haloes and cross round the moon are caused by the passage of her light through a tissue of impalpably minute needle-like crystals of ice slowly falling through the atmosphere. . . . In summer the sun was often surrounded by a similar meteor, but intensely dazzling, and tinted with colors like an outside rainbow.”

As their expedition begins, every detail seems to emphasize the boyish excitement of Moss’ comrades. When the summer brings endless midnight sun, some sailors find themselves passing days at a time without sleep. Even the exhaustion and isolation of ocean travel does not send the mesmerized sailors to bed, captivated, as they are, by the natural landscapes. Ice floes, stretching for miles in every direction, shine kaleidoscopically: “pink and metallic, green, pale yellow, and violet… like fields of mother-of-pearl”. And alongside the awe felt toward an inhospitable Arctic, a reader is met with the adrenaline of discovery, and a desire for ownership over what was formerly unknown. “When we stopped to secure a sketch, the lifeless stillness… was most impressive”, writes Moss: “No human eye had ever looked upon it before. And now there was neither bird or beast, or even flower or blade of grass, to dispute possession”. In this way, the sketches and chromolithographs became akin to laying claim over the land, an artistic gesture that reproduced natural beauty in order to seize it for oneself and nation.

The British Arctic Expedition was not unique in its brutality. Perhaps invigorated by the perceived violence of their environment, the men fought back. In hopes of expanding England’s contribution to natural history, they captured, bottled, and preserved everything from brittle feather stars to small black spiders. And what they didn’t capture for study, they killed en masse to consume. Carrying Winchester repeating rifles — “murderous weapons for this sort of work” — the men hunt everything that moves. Arctic hares, reindeer, walruses, and seals, which they grimly nickname “floe-rats”. In a particularly successful outing, Moss describes the midnight pursuit and overpowering of seven burly musk oxen. One man, thinking himself rather clever, tried to make a wounded ox “carry his own beef”, and guided it onto the deck of the ship while the animal could still walk. Moss notes that, although these oxen had likely never seen a human before, they understood instinctively to be afraid.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

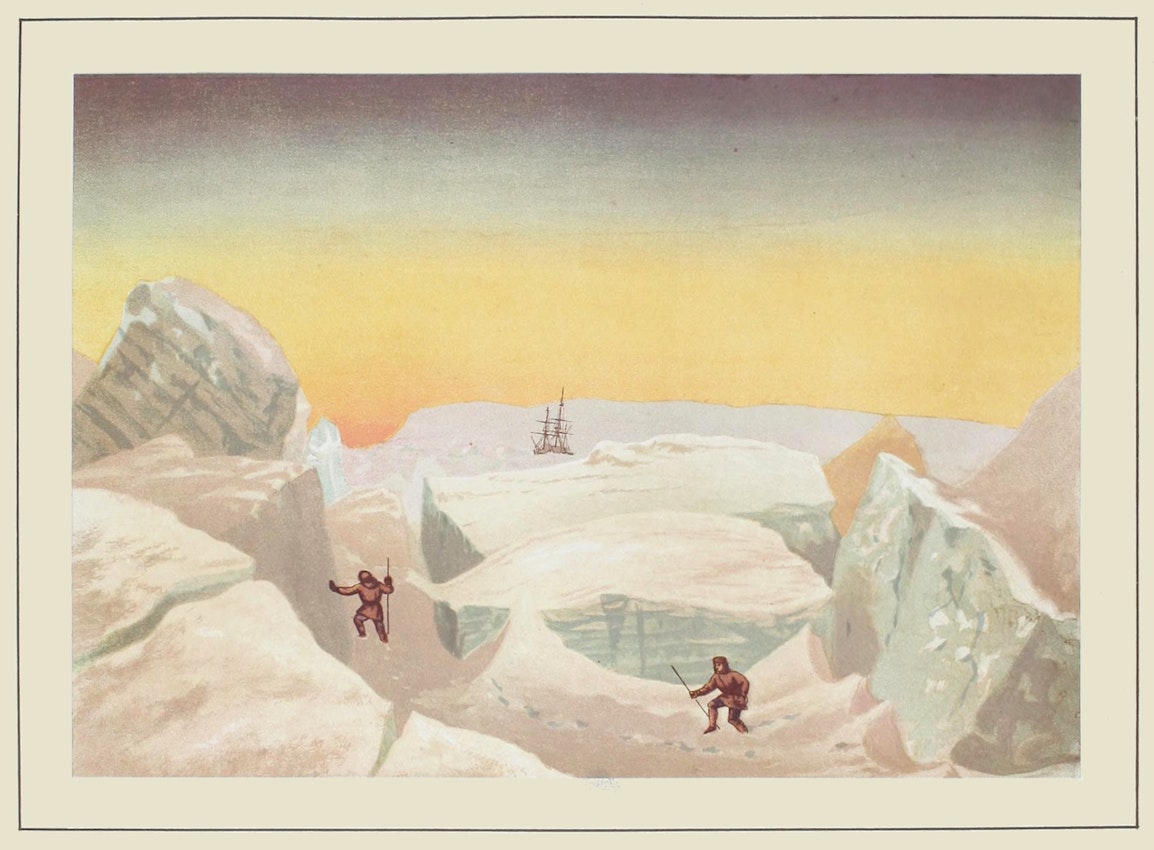

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“The sketch is from amongst Floebergs to seaward of the ship. The sides of the berg in the centre have been worn into columns and alcoves by the surface floods of some former summer. . . Snow-drifts fill up all the gorges and ravines amongst the bergs, and are in some places so hardened by wind and infiltration of sea-water, that tidal motion cracks and fissures them, especially round the grounded bergs.”

As the winter encroached, so did a seemingly permanent darkness. Fearful of the perennial ice floes, which could easily crush whatever ship crossed their path, the Alert landed at Floeberg Beach, where it would rest until the following summer allowed for safe escape. And while the daily life of a sailor may appear unsympathetic, Moss’ prose is deeply personal, poetic, and even romantic. Not only are his accounts of the expedition unflinchingly thorough, they also linger playfully on every odd moment, awkward bit of dialogue, or alienating aspect of harsh Arctic life. Through dreamlike sketches and descriptions, Moss depicts the process of building igloos to house special scientific instruments. Here, the men could sit for hours collecting data, protected from the wind and provided with an influx of dull heat from the earth. Because of the near constant snowfall, their igloos became quickly submerged, and “long before winter had passed, [the] town had disappeared as completely as Nineveh or Pompeii. Only an uncertain mound here and there projected over the bleak slope of drifted snow”. Inside their buried, makeshift town, the space reverberated with the sound of footfall overhead: the heavy steps of men, and the faster patter of paws. Often, it smelled strongly of burnt candles, and the moonlight filtering through the ice would create a greenish-blue effect, “like a diver sees deep underwater”.

Throughout this frosted travelogue, we can imagine how frantically Moss might have worked to make his landscape images come to life. Crawling up from the eternal dampness of his quarters, he would hasten across the ice to gain perspective on the ship or the igloos or the men, and maneuver his pencil through “two pairs of worsted mittens”. Once the sketch was laid, he would scurry inside to add color by candlelight, emerge again to check for accuracy, and repeat the process several more times.