Agnes Giberne’s The Story of the Sun, Moon, and Stars (1898)

On a frosty East Midlands morning, when Agnes Giberne was but seven or eight years old, she asked her father why it wasn’t warmer. She already knew, after all, that the Sun was some three million miles nearer in winter than during the summer months. Sitting across from a roaring fire in the hearth, her father pointed to a fly on his knee and replied with his own question: “See — if that fly were one inch nearer to the fire, would it feel any hotter?”

Distance — immeasurable, humbling, stupefying distance — is the leitmotif of Agnes Giberne’s 1879 Sun, Moon, and Stars: A Book for Beginners. This text is less a Victorian astronomy primer than the foundation for a phenomenological star wisdom. Remaining in print for nearly a century, it remains a compelling narrative that transports us to the most remote astral bodies, but also quickens every reader’s lost seven-year-old sensibility that the universe was made to be brought within one’s humble yet unbounded reach. The method of her father’s koan-like response — simple, striking analogy — would become Giberne’s own foolproof method to ask immense questions about the Earth’s history, atmosphere, oceans, vegetation, and, especially, the starry heavens above.

The answer to her book’s opening question (“What is this earth, of ours?”) promises that no matter how immense and incomprehensible it may appear, Earth is “Something very great — and yet something very little. Something very great, compared with the things upon the earth; something very little, compared with the things outside the earth.” Employing always the inclusive “we” in her wide-ranging narrative, Giberne’s poetic voice swings gently between wide-eyed wonder and hard-nosed empiricism. She compasses the Earth as one sibling in the solar system “family”, embraces each planet as a beautiful and mysterious bosom friend, and rocks the reader not to sleep but to wakefulness in the Cosmos.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.When Sun, Moon and Stars appeared in 1879, Agnes Giberne had published thirty-five works of Victorian evangelical fiction. In the original and subsequent editions until 1898, when it was repackaged as The Story of the Sun, Moon, and Stars, each chapter came prefaced by Bible passages, with God’s hand everywhere invoked. This was hardly a contradiction. For years, Giberne had carried on a lively correspondence about how to reconcile Biblical miracles and modern natural science’s materialist gospel with University of Oxford observatory director Charles Pritchard, who wrote an admiring preface for Giberne’s pioneering venture: a layperson’s guide to astronomical science.

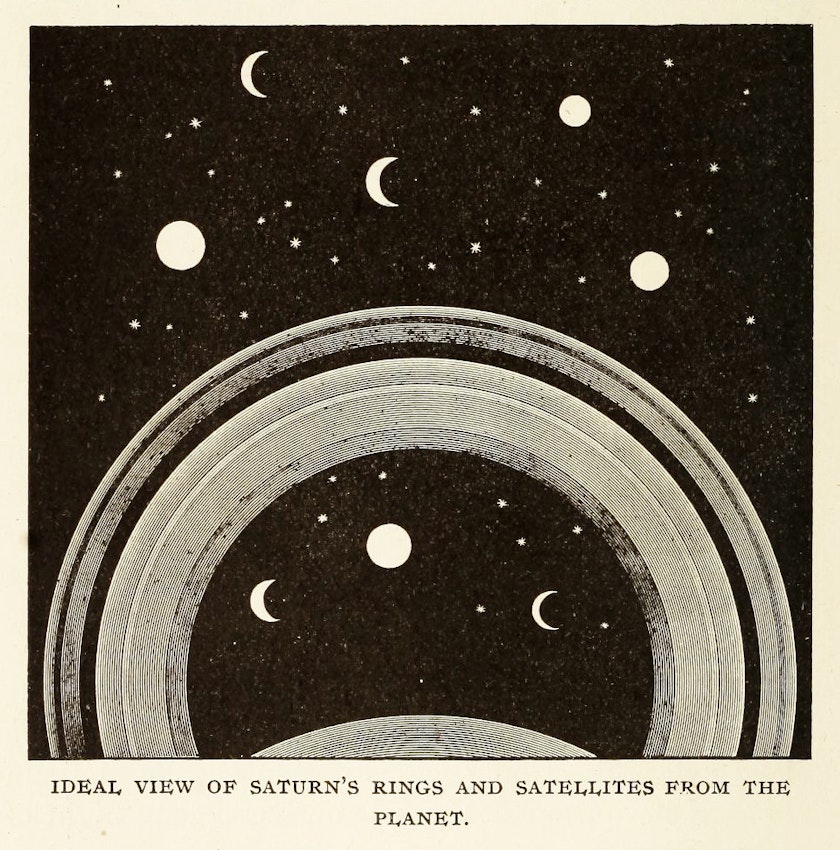

Despite its title’s inviting offer of a “story”, the 1898 edition featured-above — while retaining nearly the entirety of Giberne’s 1879 narrative, with “Copious Additions” of wonderful silhouette woodcuts — is recognizably more modern and more “scientific”. Revisions include new sections on the technology of stellar photography, a capsule history of (male) astronomers, and the deletion of all the Biblical passages and half of the enthusiastic outbursts acknowledging God’s benevolent intelligence. One feels in the arc of these changes the process of celestial disenchantment that was accelerating as the nineteenth century closed. In 1898 the world’s attention turned to speculation about life on Mars and the Moon, fueling both literary fantasy and astronomical exploration. Agnes Giberne’s goal — to foster soulful intimacy with the solar system and the stars beyond through perceptual practice and pedagogy — gave way instead to a largely alienating, technologically-driven, and competitive professional astronomy, increasingly inaccessible to interested amateurs. Reading her wonderful book now, in any edition, one returns to a lost world: the forgotten cosmos of childlike curiosity.