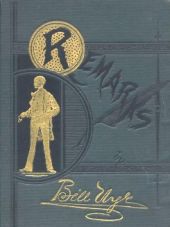

Remarks

by Bill Nye

After I had accumulated a handsome competence as city editor of the old Morning Sentinel at Laramie City, and had married and gone to housekeeping with a gas stove and other luxuries, my place on the Sentinel was taken by a newspaper man named Hopkins, who had just graduated from a business college, and who brought a nice glazed grip sack and a diploma with him that had never been used.

Hopkins wrote a fine Spencerian hand and wore a black and tan dog where-ever he went. The boys were willing to overlook his copper-plate hand, but they drew the line at the dog. He not only wrote in beautiful style, but he copied his manuscript, so that when it went in to the printer it was as pretty as a wedding invitation.

Hopkins ran the city page nine days, and then he came into the city hall where I was trying a simple drunk and bade me adieu.

I just say this to show how difficult it is for a fine penman to get ahead as a journalist. Of course good, readable writers like Knox and John Hancock may become great, but they have to be men of sterling ability to start with.

I have some of the most bloodcurdling horrors preserved for the purpose of showing Hopkins’ wonderful and vivid style. I will throw them in.

“A little son of our esteemed fellow townsman, J.H. Hayford, suffered greatly last evening with virulent colic, but this A.M., as we go to press, is sleeping easily.”

Think of shaking the social foundations of a mountain mining and stock town with such grim, nervous prostrators as that! The next day he startled Southern Wyoming and Northern Colorado and Utah with the maddening statement that “our genial friend, Leopold Gussenhoven’s fine, yellow dog, Florence Nightingale, had been seriously threatened with insomnia.”

That was the style of mental calisthenics he gave us in a town where death by opium and ropium was liable to occur, and where five men with their Mexican spurs on climbed one telegraph pole in one night and sauntered into the remote indefinitely. Hopkins told me that he had tried to do what was right, but that he had not succeeded very well. He wrung my hand and said:

“I have tried hard to make the Sentinel fill a long want felt, but I have not been fortunate. The foreman over there is a harsh man. He used to come in and intimate in a frowning and erect tone of voice, that if I did not produce that copy p.d.q., or some other abbreviation or other, that he would bust my crust, or words of like import.

“Now that’s no way to talk to a man of a nervous temperament who is engaged in copying a list of hotel arrivals, and shading the capitals as I was. In the business college it was not that way. Everything was quiet, and there was nothing to jar a man like that.

“Of course I would like to stay on the Sentinel and draw the princely salary, but there are two hundred reasons why I cannot do it. So far as the physical effort is concerned, I could draw the salary with one hand tied behind me, but there is too much turmoil and mad haste in daily journalism to suit me, and another thing, the proprietor of the Sentinel this morning stole up behind me and struck me over the head with a wrought-iron side stick weighing ten pounds. If I had not concealed a coil spring in my plug hat, the blow would have been deleterious to me.

“Then he threw me out of the door against a total stranger, and flung pieces of coal at me and called me a copper-plate ass, and said that if I ever came into the office again he would assassinate me.

“That is the principal reason why I have severed my connection with the Sentinel.”

As he said this, Mr. Hopkins took out a polka-dot handkerchief wiped away a pearly tear the size of a walnut, wrung my hand, also the polka-dot wipe, and stole out into the great, horrid hence.

Continue...

Continue...![[Buy at Amazon]](../images.amazon.com/images/P/B000875S1G.01.MZZZZZZZ.gif)