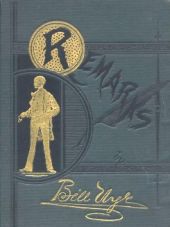

Remarks

by Bill Nye

Hudson, Wis., January 19, 1886.

Dear friend.–I have just received your kind and cordial invitation to come to Washington and spend several weeks there among the eminent men of our proud land. I would be glad to go as you suggest, but I cannot do so at this time. I am passionately fond of mingling with the giddy whirl of good society. I hope you will not feel that my reason for declining your kind invitation is that I feel myself above good society. I assure you I do not.

Nothing pleases me better than to dress up and mingle among my fellow-men, with a sprinkling here and there of the other sex. It is true that the most profitable study for mankind is man, but we should not overlook woman. Woman is now seeking to be emancipated. Let us put our great, strong arms around her and emancipate her. Even if we cannot emancipate but one, we shall not have lived entirely for naught.

I am told by those upon whom I can rely that there are hundreds of attractive young women throughout our joyous land who have arrived at years of discretion and yet who have never been emancipated. I met a woman on the cars last week who is lecturing on this subject, and she told me all about it. Now, the question at once presents itself, how shall we emancipate woman unless we go where she is? We must go right into society and take her by the hand and never let go of her hand till she is properly emancipated. Not only must she be emancipated, but she must be emancipated from her present thralldom. Thralldom of this kind is liable to break out in any community, and those who are now in perfect health may pine away in a short time and flicker.

My course, while mingling in society’s mad whirl, is to first open the conversation with a young lady by leading her away to the conservatory, where I ask her if she has ever been the victim of thralldom and whether or not she has ever been ground under the heel of the tyrant man. I then time her pulse for thirty minutes, so as to strike a good average. The emancipation of woman is destined at some day to become one of our leading industries.

You also ask me to kindly lead the German while there. I would cheerfully do so, but owing to the wobbly eccentricity of my cyclone leg, it would be sort of a broken German. But I could sit near by and watch the game with a furtive glance, and fan the young ladies between the acts, and converse with them in low, earnest, passionate tones. I like to converse with people in whom I take an interest. I was conversing with a young lady one evening at a recherche ball in my far away home in the free and unfettered West, a very brilliant affair, I remember, under the auspices of Hose Company No. 2, I was talking in a loud and earnest way to this liquid-eyed creature, a little louder than usual, because the music was rather forte just then, and the base viol virtuoso was bearing on rather hard at that moment. The music ceased with a sudden snort. And so did my wife, who was just waltzing past us. If I had ceased to converse at the same time that the music shut off, all might have been well, but I did not.

Your remark that the president and cabinet would be glad to see me this winter is ill-timed.

There have been times when it would have given me much pleasure to visit Washington, but I did not vote for Mr. Cleveland, to tell the truth, and I know that if I were to go to the White House and visit even for a few days, he would reproach me and throw it up to me. It is true I did not pledge myself to vote for him, but still I would hate to go to a man’s house and eat his popcorn and use his smoking tobacco after I had voted against him and talked about him as I have about Cleveland.

No, I can’t be a hypocrite. I am right out, open and above board. If I talk about a man behind his back, I won’t go and gorge myself with his victuals. I was assured by parties in whom I felt perfect confidence that Mr. Cleveland was a “moral leper,” and relying on such assurances from men in whom I felt that I could trust, and not being at that time where I could ask Mr. Cleveland in person whether he was or was not a moral leper as aforesaid, I assisted in spreading the report that he had been exposed to moral leprosy, and as near as I could learn, he was liable to come down with it at any time.

So that even if I go to Washington I shall put up at a hotel and pay my bills just as any other American citizen would. I know how it is with Mr. Cleveland at this time. When the legislature is in session there, people come in from around Buffalo with their butter and eggs to sell, and stay overnight with the president. But they should not ride a free horse to death. I may not be well educated, but I am high strung till you can’t rest Groceries are just as high in Washington as they are in Philadelphia.

I hope that you will not glean from the foregoing that I have lost my interest in national affairs. God forbid. Though not in the political arena myself, my sympathies are with those who are. I am willing to assist the families of those who are in the political arena trying to obtain a precarious livelihood thereby. I was once an official under the Federal government myself, as the curious student of national affairs may learn if he will go to the Treasury Department at Washington, D.C., and ask to see my voucher for $9.85, covering salary as United States commissioner for the Second Judicial District of Wyoming for the year 1882. It was at that time that a vile contemporary characterized me as “a corrupt and venal Federal official who had fattened upon the hard-wrung taxes of my fellow citizens and gorged myself for years at the public crib.” This was unjust I was not corrupt I was not venal. I was only hungry!

Continue...

Continue...![[Buy at Amazon]](../images.amazon.com/images/P/B000875S1G.01.MZZZZZZZ.gif)